timeline of Frederick Douglass

and family

1818. (Exact

date unknown) Frederick Douglass is born as Frederick Augustus

Washington Bailey, a slave at Holme Hill Farm, Talbot County,

Maryland.

His mother, Harriet Bailey, was a field slave from whom he was

separated during his infancy. Douglass only saw his mother four

or five times thereafter and for only a few hours each time. She

had been sold to a man who lived twelve miles from where Douglass

lived, and to see her son required that after her day's work in

the field she walk the twelve miles, visit with him for a short

time during the night, walk the twelve miles back to her home,

and work a second day in the fields without rest. She died when

Douglass was about seven.

Douglass never knew for certain whom his father was. He did know

that his father was white, and he believed he was his master,

Aaron Anthony.

1826. Sent to

live with Hugh Auld family in Baltimore.

1827. Asks Sophia

Auld to teach him his letters. Hugh Auld stops the lessons because

he feels that learning makes slaves discontented and rebellious.

1834. Hired Out

to Edward Covey, a "slave breaker", to break his spirit

and make him accept slavery.

1836. Tries to

escape from slavery, but his plot is discovered.

|

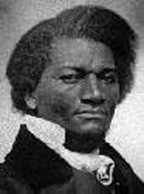

Frederick Douglass

|

1836-38. Works

in Baltimore shipyards as a caulker. Falls in love with Anna

Murray, a free Negro (daughter of slaves).

1838. Douglass

escapes from slavery and goes to New York City. Marries Anna

Murray.

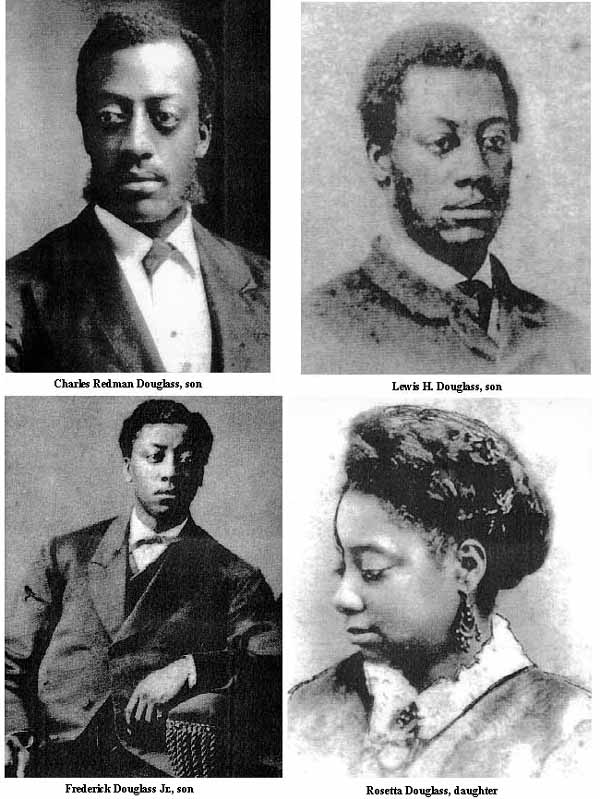

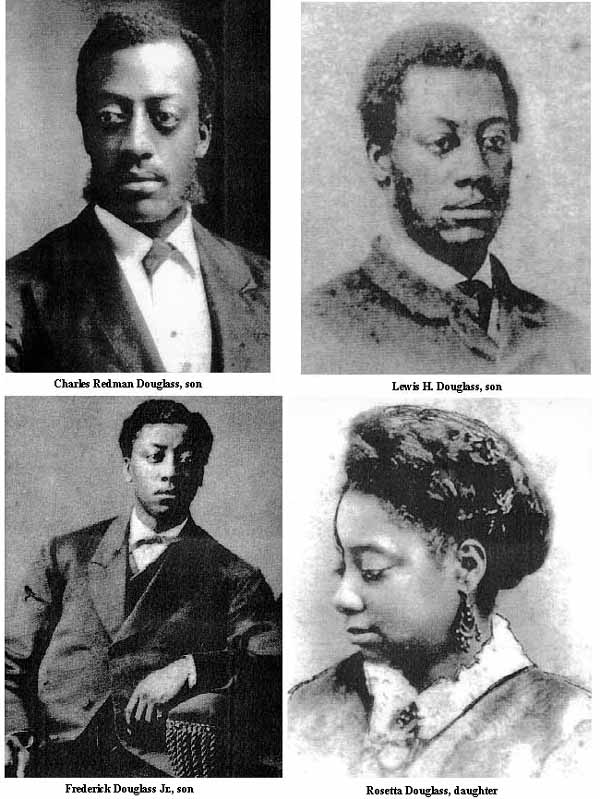

1839. Doughter

Rosetta (1839 - 1906) is born. Frederick subscribes to William

Garrison's The Liberator.

|

Anna Murray Douglass

|

1840. Son Lewis

Henry (1840 - 1908) is born.

1841. Speaks

at a meeting of the Bristol Anti-Slavery Society, and subsequently,

at the urging of William Lloyd Garrison, Douglass became a lecturer

for the American Anti-Slavery Society and travels widely in the

East and Midwest lecturing against slavery and campaigning for

rights of free Blacks.

1842. Son Frederick

Douglass, Jr. (1842 - 1892) is born.

1843. Organized

by Abner A. Frances, Henry Moxley (see 1832), the Charles L. Reason (the first

Black math professor at a white college), and others, a National

Convention of Colored Men was held in Buffalo to find ways to

end slavery. The keynote speaker, Samuel H. Davis of Buffalo,

called on northern Blacks to take part in the great battle for

our rights in common with other citizens of the United States.

Meeting in Buffalo around the same time was the abolitionist National

Convention of the Liberty Party. However, William Wells Brown

did not trust the Liberty Party, a white man's organization (see

1836).

Frederick Douglass attended both conventions.

He reports:

For nearly a week I spoke every day in this old post office

to audiences increasing in numbers and respectibility til the

[Michigan Avenue] Baptist church was thrown open to me. When

this became too small I went on Sunday into the open park and

addressed an assembly of 4,000 persons. [Goldman]

1844. Son Charles

Remond (1844 - 1920) is born.

1845. Publishes

the first of three autobiographies: The

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave.

To escape recapture following publication, goes to England lecturing

on the American anti-slavery movement throughout the British Isles.

1846. Becomes

legally free when British supporters purchase his freedom from

Hugh Auld, his former master.

1847a. Frederick

and Anna Murray Douglass, attracted by Susan B. Anthony's very

active women's movement, moved their family (8 year old Rosetta,

7 year old Lewis, 5 year old Frederick, and 3 year old Charles)

to Rochester New York. Even their prejudice forced the Douglass'

children to be educated elsewhere.

The presence of Frederick Douglass, a famous

ex-slave who became a prominent abolitionist, publisher and spokesman

against slavery, helped to enhance Rochester's reputation as a

liberal minded city. In fact, Douglass used his own Rochester

home as one of the stops used for fugitive slaves.

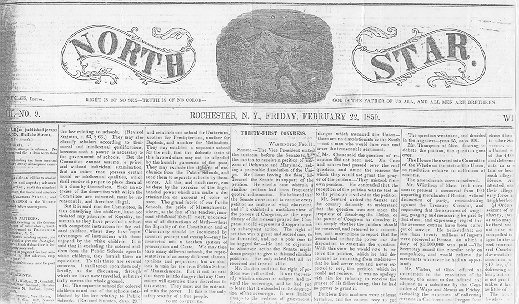

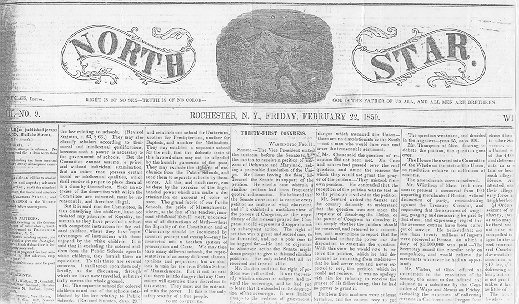

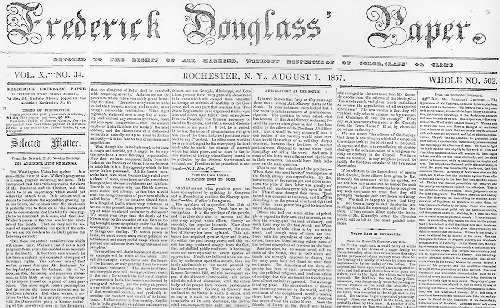

1847b. Martin

R. Delany moves from Pittsburgh to Rochester in order to found

with and work with Frederick Douglass and William Cooper Nell

on a new paper, North Star, printed in the basement of

Memorial African Methodist Episcopal Zion church, a flourishing

center for "underground" activities. Some local citizens

were unhappy that their town was the site of a black newspaper,

and the New York Herald urged the citizens of Rochester to dump

Douglass's printing press into Lake Ontario. Gradually, Rochester

came to take pride in the North Star and its bold editor. starting

the North Star marked the end of his dependence on Garrison and

other white abolitionists. The paper allowed him to discover the

problems facing blacks around the country. Douglass had heated

arguments with many of his fellow black activists, but these debates

showed that his people were beginning to involve themselves in

the center of events affecting their position in America. [Rollin]

|

|

|

Once the North Star began to circulate,

Douglass's friends in the abolitionist movement rallied to join

in praising it. However, not everyone was pleased to see another

antislavery paper - especially one edited by an ex-slave. Some

local citizens were unhappy that their town was the site of a

black newspaper, and the New York Herald urged the citizens

of Rochester to dump Douglass's printing press into Lake Ontario.

Gradually, Rochester came to take pride in the North Star

and its bold editor.

The town had a reputation for being pro-abolitionist.

Rochester's women were active in antislavery societies, and through

them Douglass kept in close contact with the leaders in the fight

for women's rights, among them Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott,

and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Along with the good will of Rochester's

abolitionist and female political activists, Douglass received

encouragement from the local printer's union. The North Star

received a number of glowing reviews, but unfortunately the praises

did not translate into financial success. The cost of producing

a weekly newspaper was high and subscriptions grew slowly. For

a number of years, Douglass was forced to depend on his own savings

and contributions from friends to keep the paper afloat. He was

forced to return to the lecture circuit to raise money for the

paper. During the paper's first year, he was on the road for

six months. In the spring of 1848, he had to mortgage his home.

In the midst of these troubles, a friend from

England arrived to help Douglass with his financial problems.

Julia Griffiths had raised enough money to help launch the paper,

and now she was prepared to fight for its survival. Griffiths

put the North Star's finances in order, and Douglass was

eventually able to regain possession of his home. By 1851, he

would be able to write to his friend, the abolitionist publisher

and politician Gerrit Smith, "The North Star sustains

itself, and partly sustains my large family. It has reached a

living point. Hitherto, the struggle of its life has been to

live. Now it more than lives." Despite the ups and downs,

Douglass's newspaper continued publication as a weekly until

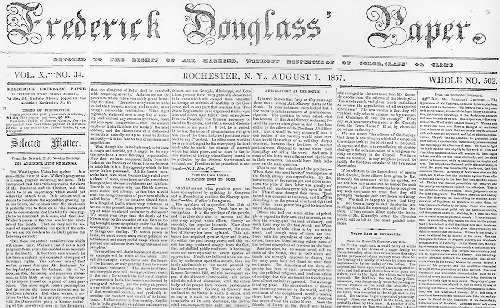

1860 and survived for three more years as a monthly. After 1851,

it would be titled Frederick Douglass' Paper. Douglass's

newspaper symbolized the potential for blacks to achieve whatever

goals they set. The paper provided a forum for black writers

and highlighted the success achieved by prominent black figures

in American society.

The paper survived as a weekly until 1860

and then for three more years as a monthly.

|

1848. Douglass attends the first women's rights convention

at Seneca Falls, NY and advocates the right to vote for women.

While he roamed far beyond his original bounds, his wife, though

hard-working, remained uneducated and politically unambitious.

In England he met Julia Griffiths and brought her home to live

with him in the Rochester family house as a tutor for his children

and for wife Anna in 1848. But his effort with his wife failed

and Anna remained almost totally illiterate until her death.

A scandal erupted when Julia Griffiths began

to serve as Douglass's office and business manager and soon became

his almost constant companion. She arranged his lectures, dealt

with the paper's finances and accompanied him to meetings. People

in Rochester gradually adjusted to the sight of the black leader

and the white woman walking arm in arm down the street.

1849a. Annie

Douglass, Frederick's last child, is born.

1849b. On May

5 Douglass is attacked by gang of toughs when he walks along Battery

in New York City with two British women friends, Julia and Eliza

Griffiths.

1850a. Publishes

an attack on the Compromise of 1850 and the new fugitive-slave

law.

1851a. Changes

the name of North Star to Frederick Douglass' Paper. Helps

three fugitive Maryland slaves escape to Canada as "Station

Master" of the Rochester terminus of the Underground Railroad(read more).

1851b. Julia

Griffiths helped put the 'North Star's' finances in order.

Julia Griffiths was one of six founders of

the Rochester

Ladies' Anti-Slavery and Sewing Society. The "Sewing"

was later dropped. By March, 1852, the Society had grown to nineteen

members, when they held the first of their Festivals, or bazaars.

In these events, held annually for over a decade, the women of

the Society raised money through the sale of items made locally

or contributed by other anti-slavery societies as far away as

Britain, and through gate receipts for lectures by Frederick Douglass,

Gerrit Smith, or other activists held in the Corinthian Hall.

The first Festival was advertised in newspapers as far away as

New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C., and by all accounts,

it was a rousing success, netting over $250. Following on the

heels of this bazaar, the Society intensified their fund raising

efforts, matching success with success. In 1853, Julia Griffiths

edited Autographs for freedom, a collection of antislavery

essays by William Wells and Black mathematician Charles

Reason and others, with facsimile signatures of the contributors,

which sold so well that a second edition was prepared the following

year. In the winter of 1854-55, the Society also sponsored its

first annual lecture series, bringing in renowned speakers. Once

again, the Society found a large and receptive audience for their

message. Colleagues in British antislavery societies provided

an important and regular source of funds through bazaars held

on behalf of the Rochester Society. By the late 1850s, the annual

receipts of the Society surpassed $1,500.

The bulk of the money raised by the Society

was used in the important task of keeping Frederick Douglass'

Paper solvent, but money was also used to help support a school

for freedmen in Kansas and for the publication and distribution

of anti-slavery literature in Kentucky. The Society played a crucial

support role in one stretch of the Underground Railroad, providing

small cash gifts directly to fugitive slaves to aid them on the

last leg of their escape to Canada. The Society's annual reports

for 1855 and 1856 listed 136 fugitives who had passed through

Rochester with the Society's help, and by the following year,

they had begun to develop a connection with veteran "railroad"

engineer, Harriet Tubman.

The pro-slavery pessure and Black and White lover scandal became

too much and in 1855 Julia Griffiths returned to England and got

married

1851c. Douglass

aids three fugitive Maryland slaves, wanted for murdering their

former master when he tried to recapture them in Pennsylvania

in escaping to Canada. The three are among hundreds Douglass helps

flee to freedom as "station master" of the Rochester

terminus of the Underground Railroad.

1852a. Splits

with Garrison over the means to achieve the abolition of slavery.

Chosen vice-presidential candidate at the Liberal Party convention.

Delivers his famous speech, "What to the Slave is the Fourth

of July?" in Corinthian Hall, Rochester, New York.

1852b. Griffiths

decided to spare Douglass further embarrassment by moving out

of his home. She remained his close associate until she left the

United States.

1853. With Frederick

Douglass as a draw, the National Negro Convention (also known

as the Colored National Convention) meets in Rochester.

1855a. Douglass

writes a second autobiography: My Bondage and My Freedom.

1855b. Aware

that Douglass' enemies were using his highly public relationship

with Griffith as negative fodder, Julia Griffith returns home

to England.

|

1855c. Douglass meets Ottilie Assing. Ottilie (1819-1884)

was a German (half-Jew) journalist for the prestigious German

newspaper Morgenblatt für gebildete Leser, who traveled

to Rochester, New York, in 1856 to interview Douglass. Assing

spent the next 22 summers with the Douglass family, working on

articles, the translation project, and tutoring his children.

Anna Douglass, Frederick's wife, was somewhat

older than Frederick and illiterate, was als ill much of the

time. She shared little of her husband's intellect or interests,

and seemed unable to cope with the large household.

Assing, on the other hand, was a passionate

abolitionist, was politically astute, and contributed a great

deal to Douglass' work. The affair was never confined to the

domestic sphere, and it was never a secret. For most of their

26 year friendship, when apart, Frederick and Ottilie weekly

wrote each other. Assing was confident that, upon Anna's death,

Douglass would marry her. Oh, bitter news! He wed another woman

- white, bright and 20 years his junior. Heartbroken and ill

with breast cancer, Assing walked into a park, opened a tiny

vial and swallowed the potassium cyanide within. Still Ottilie

left Frederick Douglass as the sole heir in her will.

|

Ottilie Assing

|

[Note. The Douglass's letters to Assing were burned, and only

a handful survive from Assing to Douglass. There is a book by

a professor of American Studies at University of Muenster in Germany: Love

across Color Lines: Ottilie Assing and Frederick Douglass.

By Maria Diedrich. (New York: Hill and Wang, 1999. xxx, 480 pp.

$35.00, isbn 0-8090-1613-3.) ]

1857. The Rochester

public schools desegregate after years of Frederick Douglasses

protestations.

1858. John Brown

stays at the Douglass home in Rochester while developing plans

for encouraging a slave revolt.

1859a. Escapes

to Canada to avoid being arrested as an accomplice in John Brown's

plan to seize Harper's Ferry and sails to England:

Douglass knew and supported John Brown in his assisting escaped

slaves to reach Canada. But when in 1859 Brown told him of the

plan to assault the Harpers Ferry Arsenal and to arm the slaves

for an insurrection, Douglass knew that his friend had gone round

the bend and declined to participate in the raid. Brown's confiscated

papers mentioned the name of Douglass, and a request for his arrest

was issued. This led Douglass to take an immediate unplanned voyage

to Europe, where he met up with Ottilie Assing, and, on the lecture

circuit he acclaimed, from afar, the martyrdom of John Brown.

1859b. Ottilie

Assing, vividly described for a German paper, a demarcation line

that surrounded Douglass's home: "This is the house of FD,

the famous colored orator, who lives in the country close to Rochester

, and American color prejudice is the demon which surrounds this

house like a Chinese wall, beyond which only the most determined

and ardent abolitionists dare to step."

1859c. Eleven-year

old daughter Annie Douglass dies.

1860. Returns

to the United States upon hearing of the death of his, Annie.

Her death had the effect of curtailing Douglass' European speaking

tours.

1861. Calls for

the use of Black troops to fight the Confederacy through the establishment

of Negro regiments in the Union Army.

1863a. Congress

authorized black enlistment in the Union army. The Massachusetts

54th Regimate was the first black unit to be formed, and the governor

of the state asked Frederick Douglass to help in the recruitment.

Douglass agreed and wrote an editorial that was published in the

local newspapers. "Men of Color, to Arms," he urged

blacks to "end in a day the bondage of centuries" and

to earn their equality and show their patriotism by fighting in

the Union cause. His sons Lewis and Charles were among the first

Rochester African Americans to enlist. Douglass visited President

Abraham Lincoln to protest discrimination against Black troops.

1863b. Rosetta

Douglass , daughter of Frederick, returns to Rochester with new

husband Nathaniel Sprague.

1863c. Douglass

visits President Lincoln, protests discrimination against black

troops; visits President Lincoln in White House to plead the case

of the Negro soldiers discriminated against in the Union army;

receives assurance from Lincoln that problem will be given every

consideration; visits secretary of War Stanton and assured that

he will receive a commission in Union Army to Recruit Negro soldiers

in South.

1864. Frederick

Douglass served as an adviser to President Abraham Lincoln during

the Civil War and fought for the adoption of constitutional amendments

that guaranteed voting rights and other civil liberties for blacks.

Douglass provided a powerful voice for human rights during this

period of American history and is still revered today for his

contributions against racial injustice.

1865. Douglass

speaks at memorial meeting on life and death of Lincoln called

by Negroes of New York City after New York Common Council refused

to permit Negroes to participate in the funeral procession when

Lincoln's body passed through the city. Later Mrs. Lincoln sends

him the martyred president's walking stick.

1866. Attends

convention of Equal Rights Association and clashes with women's

rights leaders over their insistence that the vote not be extended

to Black men unless it is given to all women at the same time.

1867. Turns down

President Andrew Johnson's offer to name him commissioner of the

Freedmen's Bureau inasmuch as the National Black Leadership supported

General Oliver O. Howard's continuation in the post.

1869. Frederick's

son Lewis marries Amelia Loguen, daughter of Bishop Jermain

Loguen.

1870. Becomes

owner and editor of The New National Era, a weekly newspaper in

Washington. DC.

1871. Appointed

Assistant Secretary to the Conimission of Inquiry into the possible

annexation of Santo Dorningo.

1872. Douglass

is nominated for vice-president by Equal Rights Party on a ticket

headed by Victoria Woodhull. During the 1872 presidential election,

and Frederick Douglass was given an unexpected honor. He was chosen

as one of the two electors-at-large from New York, the men who

carried the sealed envelope with the results of the state voting

to the capital. After the election, Douglass expected that he

would be given a position in the Ulysses S. Grant administration,

but no post was offered, so he returned to the lecture circuit.

Later Douglass's Rochester home went up in flames. None of his

family was hurt, but many irreplaceable volumes of his newspapers

were destroyed. Although friends urged him to rebuild in Rochester,

Douglass decided to move his family to the center of political

activity in Washington, D.C.

1874. Named president

of Freedman's Savings and Trust Company.

1877. Appointed

US marshall of the District of Columbia.

|

Douglass 188_

|

1878. Douglass

purchases "Cedar Hill" a 9-acre estate in the Anacostia

section of Washington, DC.

1881. Frederick

Douglass is appointed Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia.

He publishes a third autobiography: Life and Times of Frederick

Douglass.

1882a. Florence

Sprague and Viola VanBuren where the first Black teachers in

the Rochester School District. (note: it appears not to be true

that Florence is daughter of Rosetta Douglass Sprague, see 1863)

1882b. Anna

Douglass, died after a long illness.

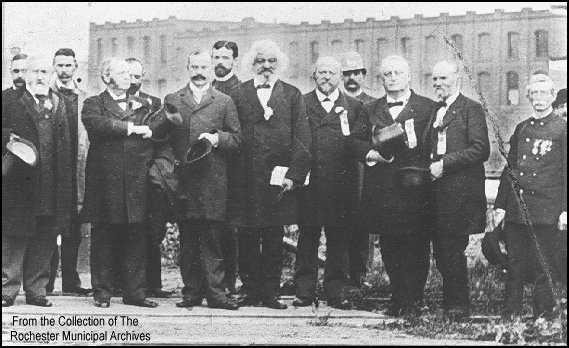

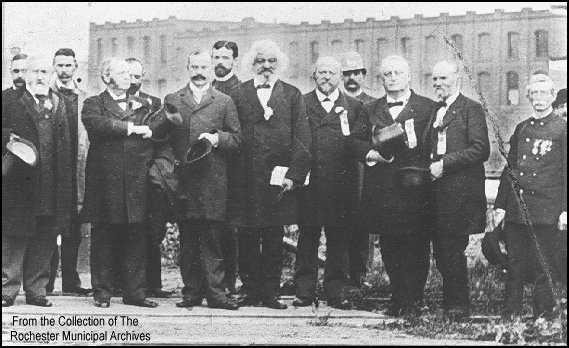

1883. Distinguished

Men of New York

|

1884a. Resigns

as Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia.

1884b. Frederick Douglass marries

his secretary Helen Pitts, a white woman from Honeoye New York

(not 20 miles distant Honeoye Falls), who was nearly 20 years

younger than he. Both families recoiled; hers stopped speaking

to her; his was bruised for they felt his marriage was a repudiation

of their mother.

|

Hellen Pitts was a graduate of Mount Holyoke

Seminary, and daughter of Gideon Pitts, Jr., an abolitionist

colleague and friend of Douglass'. Gideon's home was a station

on the Underground Railroad.. While living in Washington, D.C.

before her marriage, Helen had worked on a radical feminist publication

called the Alpha.

Helen is a direct descendent of John and Priscilla

Alden and a cousin to Presidents John and John Q. Adams.

As a result, the marriage of a Mayflower Daughter to a former

slave was yet another source of outrage to those who opposed

the inter-racial marriage with Douglass. It was Pitts' race,

and not her age upset both the black and the white communities.

Douglass' response was, My first wife was the color of my

mother, my second is the color of my father.

Pitts, nevertheless, would prove to be most

influential at establishing the Frederick Douglass home and maintaining

the legacy of Douglass after his death..

|

Helen Pitts Douglass

|

1884c. Frederick

Douglass' lover of 26 years, Ottilie

Assing commits suicide (see 1856 above).

1886. 1986-87

Frederick and Helen travel to England, France, Italy, Egypt and

Greece in 1886-87.

1888. Appointed

Consul General to Haiti by President Benjamin Harrison

1889. Appointed

Charge d'Affaires for Santo Domingo as well as Minister Resident

to Haiti.

1891. Resigns

as Minister to Haiti.

1892. Below -

President Benjamin Harrison attends ceremony at Kodak Park with

Frederick Douglass, Mayor Hiram Edgerton and Civil War veterans.

1893. Announces

plans to establish Freedom Manufacturing Co., a textile manufacturing

firm, on a site near Norfolk, Virginia, where he hopes to employ

300 blacks. The scheme proves to be a sham by unscrupulous promoters

using his name and prestige.

1895. On February

20, Frederick Douglass at Cedar Hill, Anacostia, after attending

a women's rights meeting, was struck by a massive heart attack

and died at the age of 77. As news of Douglass's death spread

throughout the country, crowds gathered at the Washington church

where he lay in state to pay their respects. Black public schools

closed for the day, and parents took their children for a last

look at the famed leader. His wife and children accompanied his

body back to Rochester, where he was laid to rest. Helen works

to preserve the Douglass home in memory of Frederick.

| The Frederick Douglass Home. At the request of Helen Pitts Douglass, Congress

chartered the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association,

to whom Mrs. Douglass bequeathed the house. Joining with the

National Association of Colored Women's Clubs, the association

opened the house to visitors in 1916. The property was added

to the National Park system on September 5, 1962 and was designated

a National Historic Site in 1988. The Frederick Douglass National

Historic Site is located at 1411 W Street, SE in Washington,

D. C. and it is opened to the public. |

|

1896. Rosetta

Douglass Sprague was a founding member of the National Association

of Colored Women.

1898. The first

monument to a black man, Frederick

Douglass (also see 1847), was

established in Rochester.

1910. While serving

as president of the Frederick Douglass Memorial Association, Mary

Talbert was responsible for the restoration of the Frederick Douglass

Home in Anacostia, Maryland. She also served as a delegate to

the International Council of Women in Norway, and lectured internationally

internationally on race relations and women's rights. For more

on Talbert click Talbert.

Children of Frederick Douglass:

Rosetta, Lewis Henry, Frederick, Jr., Charles Resmond, Annie

Mary Louise was the daughter of Charles Resmond

Douglass. Her siblings were Charles Frederick, Joseph Henry, Annie

Elizabeth, Julia Ada, Edward and Haley George.

Some references:

- Douglass, Frederick. Life and Times of Frederick Douglass:

His Early Life as a Slave, His Escape From Bondage, and His Complete

History Written by Himself. New York: Collier Books, 1962.

- Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick

Douglass an American Slave, Written by Himself. Ed. Benjamin

Quarles. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP, 1960.

- Douglass, Helen Pitts. In Memoriam: Frederick Douglass.

Freeport, N.Y.: Books for Libraries Press, 1971.

- Diedrich, Maria. Love across Color Lines: Ottilie Assing

and Frederick Douglass. Hill and Wang, 1999, 480 pp.

$35.00, isbn 0-8090-1613-3.)

- Douglass, Frederick. The Heroic Slave. (published

in Autographs for Freedom, edited Julia Griffiths [Cleveland:

John P. Jewett & Company, 1853]

- May 2003 letters from Jean Czerkas <JFCZERKAS@msn.com>.

Florence Sprague is not a child of Rosetta Douglass. Rosetta,

her husband Nathan, three of their daughters and only son are

interred in historic Mt. Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York.

There children are:

Alice Louisa; Annie Rosine; Harriet Bailey; Estelle Irene; Fredericka

Douglass; Herbert Douglass; Rosebelle Mary.

Other sites:

Frederick Douglass home.

Frederick Douglass Museum and Cultural Center.

back to African

American History of Western New York

CONTACT US